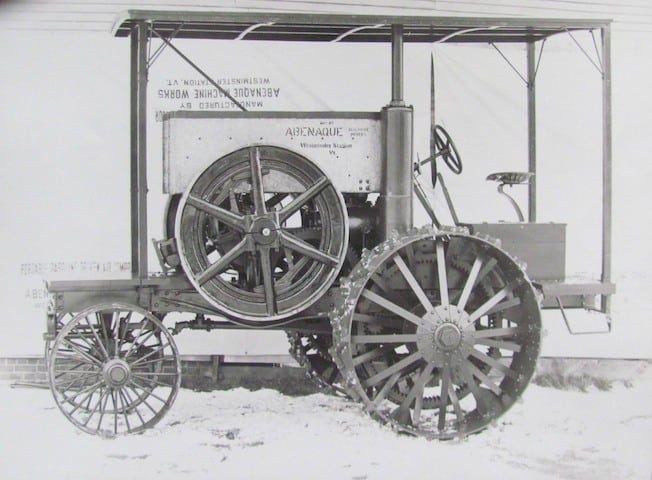

I emailed the photo you see with this article to Ted Spaulding and Danny Clemons to see what they might know. Ted has the book, “Encyclopedia of American Tractors” by C.H. Wendel. Danny found some history online.

Encyclopedia of American Tractors

This describes the tractor in the photo with this article.

“A 1911 advertisement shows great refinement over the original ‘1908 Abenaque tractor. Most obvious are the greatly strengthened rear wheels along with improved operators platform and the addition of a seat. Abenaque built a lot of quality into this tractor. It featured three forward speeds, a reverse, and sliding gear transmission.

“Steel gears were used for greater strength. The canopy shown on this model was typical of most tractors of the period. In spite of its qualities, the geographical location of the company must have been a hindrance to widespread acceptance and distribution. The company was owned by a Mr. Colgate, and later by his son Gilbert. The plant employed about 15 people.

“When Gilbert Colgate took over, he tried to modernize the plant, but soon went out of business, probably about 1916. The company then moved to Marlborough, N.H., and then only made parts.”

The 1911 tractor was a major improvement over the 1908 model. Some interesting data given for the 1908 model:

“First marketed in May, 1908 this 15 horsepower model weighed in at 11,000 pounds – over 733 pounds per horsepower. The husky chassis carried a stationary type engine that had been patented by John A. Ostenburg. The 15 horsepower model had a bore of 8 5/8 inches and a 12 1/2 inch stroke, developing its rated power at 270 RPM. Abenaque engines and tractors used a very unique and obvious evaporative cooling system. A 25 horsepower model was also offered.”

Abenaque tractors utilized one-lunger engines. Abenaque also manufactured one-lunger engines. One-lunger engines were popular on area farms. When belted to a saw rig, they proved very effective for cutting firewood. This reduced the arduous manual labor of running a bucksaw by hand. There were other applications as well. When powering a washing machine, the housewife now had a real helper. I’ve always heard hit and miss engines called one-lungers, so I use that term. Either term is correct.

For those who have heard a one-lunger engine running, no explanation is needed; but for those who haven’t heard a one-lunger, this description from Wikipedia will give you an idea.

Wikipedia

“A hit-and-miss engine or Hit ‘N’ Miss is a type of internal combustion engine that is controlled by a governor to only fire at a set speed. They are usually 4-stroke but 2-stroke versions were made. It was conceived in the late 19th century and produced by various companies from the 1890s through approximately the 1940s. The name comes from the speed control on these engines: they fire [hit] only when operating at or below a set speed, and cycle without firing [miss] when they exceed their set speed. This is as compared to the ‘throttle governed’ method of speed control. The sound made when the engine is running without a load is a distinctive ‘Snort POP whoosh whoosh whoosh whoosh snort POP’ as the engine fires and then coasts until the speed decreases and it fires again to maintain its average speed. The snorting is caused by atmospheric intake valve used on many of these engines.”

The market for these tractors were large farms on the Midwestern plains. Locally there was little demand for these tractors. The cards were stacked against Abenaque from the beginning for this reason.

Recently on the History Channel was a series, “The Machines that Built America.” I caught a couple of these programs. One program was on these early tractors. Steam-powered tractors were huge and cumbersome. Gasoline engines proved more practical. A number of inventors in the Midwest were building these tractors. Abenaque shipped their tractors by rail at the nearby Westminster Station. Manufacturers in the Midwest had a distinct advantage. If the tractor broke down, repairmen could be at your farm in no time. This was not so for Abenaque. It would take a repairman several days to reach your farm.

“Time is money” as Ben Franklin said.

Abenaque Machine Works was located at Westminster Station. If you go down Route 5 to Westminster Station, turn left through the railroad underpass. On the left was Abenaque’s place of business.

To learn more about these tractors, search online for “Abenaque Tractor.”

This week’s old saying: “A small home is better than a large mortgage.”