SPRINGFIELD, Vt. – It was a typical river cleanup – volunteers with the Black River Action Team (BRAT) were filling trash bags, pickup trucks, and boats with all manner of trash and junk they collected from the bed and banks of the Black River in Springfield, Vt. A special crew, dubbed “The Tire Brigade,” was working hard to locate and extract larger items from the lowest two miles of the river, just above its confluence with the Connecticut River.

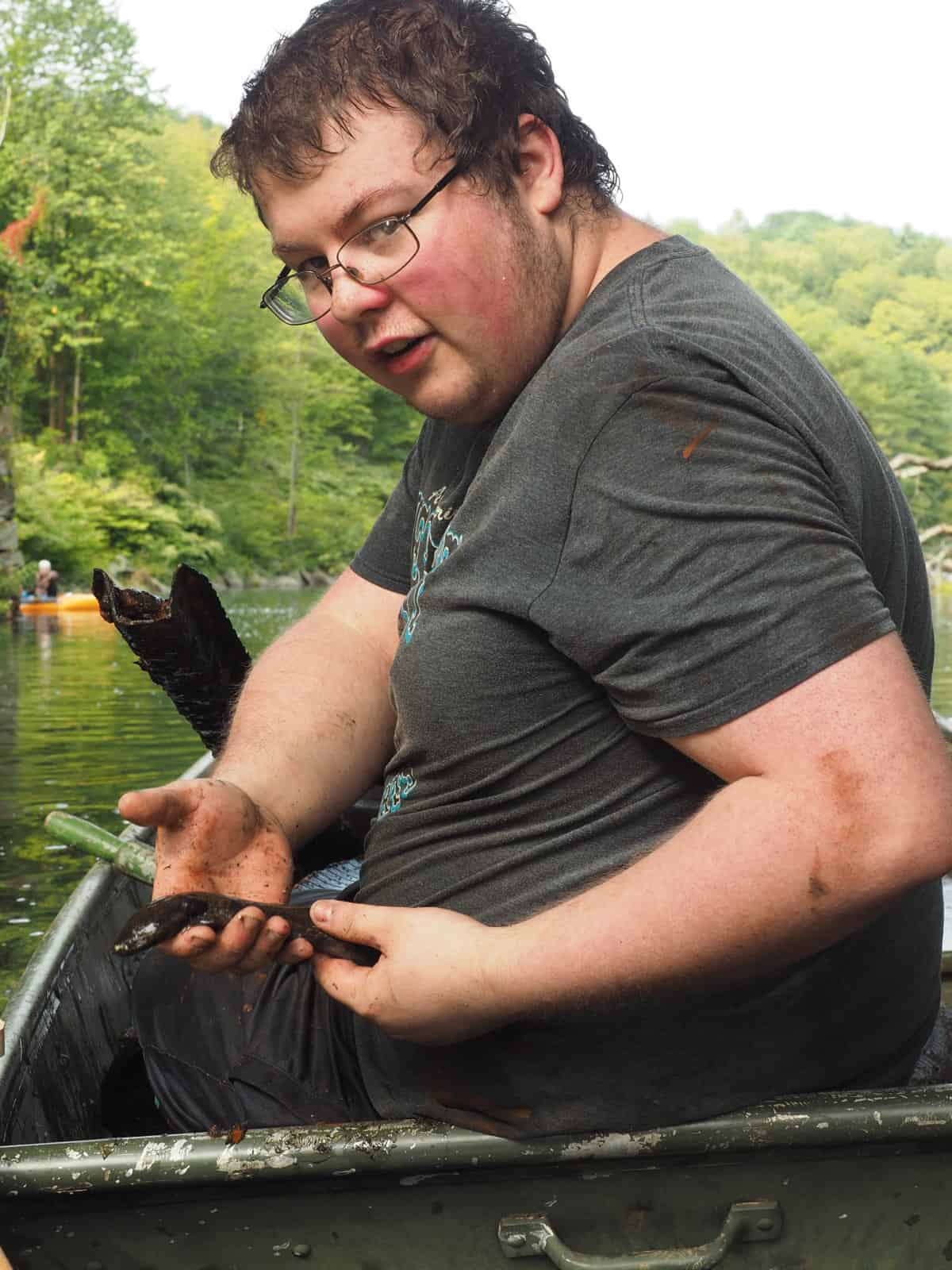

After pulling up several tires, a couple of rusted bicycles, and an extremely heavy railroad tie, the Brigade hauled up another tire, heaved it into the flat-bottomed boat, and into the hands of BRAT volunteer Lenard Barber who was waiting on board to stack it with the others. Much to Lenard’s surprise, out plopped the largest salamander he’d ever seen. Gently cradling it for a quick photo by fellow volunteer Jeff Semprebon, he carefully released it back into the water to watch it swim away.

According to herpetologist Jim Andrews, the common mudpuppy is a “pretty unusual” sight in Vermont, only found in Lake Champlain and the Connecticut River as well as the lower reaches of the tributaries to both. Yet the two populations are distinct from each other. Mark Ferguson of the VT ANR’s Wildlife Diversity Program explains: “Interestingly, mudpuppies in the Connecticut River system have long been thought to be an introduced population… related to mudpuppies from the upper Mississippi drainage or nearby. Mudpuppies in the Lake Champlain basin are native.”

Jim, director of the Vermont Herp Atlas, delivers some fun facts about these elusive giants: Some mudpuppies have lived over 30 years, eating a diet of crayfish, worms, snails, aquatic insects, other salamanders, and small fish; in a separate family from all our other salamanders, mudpuppies keep their gills, as they remain aquatic for their entire life cycle. They can take in oxygen through their thin skin, or by gulping air at the water’s surface; and, growing roughly 12 inches in length in Vermont, mudpuppies are most often reported to the State by ice fishermen, since the critters remain active throughout the winter under the ice, which is unusual for an amphibian.

Jim says that the biggest threat to mudpuppies in Vermont is the use of lampricide chemicals, such as those which have been used in the past on rivers such as the Lamoille River, which drains into Lake Champlain; however, fine sediment entering the water from erosion or storm water outfalls can also be a threat.

So keep an eye out for these “giants of the deep and not-so-deep,” and, if you do spot one, send a couple of photos to the Vermont Reptile and Amphibian Atlas at www.VtHerpAtlas.org, or just email them along with as much detail as you can, including date and exact location, directly to jandrews@vtherpatlas.org. Public observations can help determine where mudpuppies are living and what means we can take to help protect their habitat.