For 50 years I’ve bought, sold, and collected a category of early paper artifacts known as ephemera. This includes old letters and documents. A number of years ago, I bought a large lot of old documents and letters. The family was from Boston and had moved to Vermont in the late 1800s to the early 1900s.

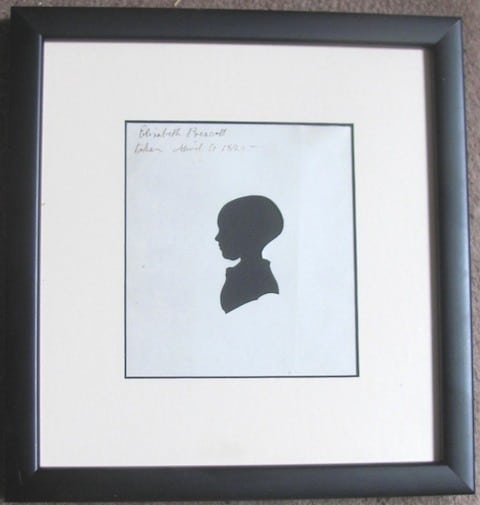

Included in that lot were Daniel Webster and Henry Clay letters. Also in this lot was the silhouette you see with this article. In the 1700s on into the early 1800s, silhouettes were a stylish way to create a likeness of a family member.

Other names for silhouettes are profiles, shadow portraits, or likeness. Supposedly silhouettes got their name from a Frenchman, Etienne Silhouette, in the 1700s. In my trade they are simply referred to as silhouettes.

During this time, silhouette portraitists sprang up in major cities specifically to create your silhouette. A silhouette is a piece of paper cut with scissors resulting in a cut out profile. In the silhouette with this article, the profile was cut from white paper. It’s delicate work but when done by a competent artist the results are beautiful.

As I said before, I found it loose in a lot of early letters – not being protected. It’s a wonder it wasn’t damaged being shuffled in a pile of letters all those years. I took it to the Framery of Vermont to be framed. As it was done in its day, I had a piece of black paper placed behind the silhouette. It is now secure.

My parents’ generation collected early American antiques including silhouettes. These are from whom I learned. There are several criteria for collecting silhouettes. First, how well done is it, of whom, and by who if known. Many sitters are unknown, but that is not the case here. Written in ink at the top left is: “Elizabeth Prescott taken April 6, 1829”

William H. Prescott

William H. Prescott, 1796 to 1859, was a Harvard graduate, an early historian, and a Hispanist. He wrote a number of histories: “The History of Ferdinand and Isabella the Catholic 1837,” “The History of the Conquest of Mexico 1843,” and “A History of the Conquest of Peru 1847.” Prescott was America’s foremost Hispanic historian of the 19th century. You can bet he held this silhouette.

Elizabeth Prescott

Elizabeth was one of his four children. She was born July 27, 1828 and died May 24, 1864. If she was born July 27, 1828, and the silhouette was taken April 6, 1829, she would have been about nine months old. Elizabeth married James Lawrence, a distant cousin.

Meaning of “taken”

Today we show friends photographs “taken” when we were on vacation. But where does the word “taken” come from? The ink inscription answers this question. I have seen other silhouettes with the notation “taken” along with a few early watercolors.

It was late 1839 to early 1840 when the first successful camera arrived in this country. These daguerreotypes, as they were known, could be purchased for as little as 25 cents. Soon having your likeness captured became the rage. As today, it is fashionable to say I bought this from so-and-so. You know what I mean, those that are currently fashionable. Silhouettes were replaced with photos from the camera.

Daguerreotypists continued to use the word “taken” for their trade. It was a familiar word to Americans at the time. Today we have our photo taken without thinking about the origin of “taken.”

Values

Like many antiques today, prices have dramatically dropped in the last 15 years. Condition is a major factor. Is the sitter known, and if so is the sitter an important figure? And lastly much scholarly work has been done regarding silhouette artists. Many have been identified. In some cases they are simply identified as Boston or Newport school. I don’t have any of these scholarly references so I can’t identify the artist.

Sometimes on the “Antiques Roadshow” a silhouette or two will surface. Sometimes these experts can identify the artist. When condition, sitter, family history, and artist all come together as they do in Elizabeth’s silhouette, these silhouettes can be quite valuable.

In the 1920s and ’30s, Americans wanted silhouettes but originals were too costly. Many companies produced inexpensive but attractive reproductions to meet this demand. While decorative, they have little value.

This week’s old saying is from Mark Twain: “A person who won’t read has no advantage over one who can’t read.”